Understanding the Gut-Brain Axis

Have you noticed that patients who present with anxiety or depression often also report gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms?

Or maybe you see patients with primary GI concerns who also report having mood imbalances or other cognitive dysfunction (i.e., brain fog, mental fatigue).

An understanding of the connection between the gut and brain has come to be known as the gut-brain axis.

Despite the broad integration of the “gut-brain” concept into our everyday vernacular (e.g., gut feeling, gut-wrenching, gut check, gut instinct, gutted, gutsy, it takes guts), neuroscientists have only recently developed adequate tools to reveal the bi-directional links between gut physiology and brain function, and to determine how these links operate under normal and stressful conditions.1

The Gut and Brain Talk to Each Other

Through multiple communication pathways, the gut-brain axis (GBA) connects the network of nerves in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract – also known as the enteric nervous system (ENS) – and the central nervous system. It is bidirectional, meaning the microbiome and gastrointestinal tract influence the brain, and the brain, in turn, affects the gastrointestinal tract.

Bidirectional communication between the gut microbiota and the central nervous system (CNS) is mediated by several direct and indirect pathways of the gut-brain axis. The routes of transmission involve

- The autonomic nervous system (for example, the ENS and the vagus nerve)

- The neuroendocrine system

- The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis

- The immune system

- Metabolic pathways2

The complex and multifaceted system of gut-brain communication ensures proper maintenance and coordination of gastrointestinal functions to support behavior and physiological processes. It also permits feedback from the gut that exerts profound effects on mood, motivated behavior, and higher cognitive functions.

The Vagus Nerve’s Role in the “Second Brain”

A vast collection of nerves (nearly 500 million) helps to control the functioning of our ENS. Often referred to as our “second brain,” this complex network controls GI motility and gastric secretions and modulates immune and endocrine functions.3

The vagus nerve carries an extensive range of signals from the digestive system and organs to the brain and vice versa. It is the tenth cranial nerve, extending from its origin in the brainstem through the neck and the thorax down to the abdomen. It is one of the biggest nerves connecting the gastrointestinal tract to the nervous system. It represents the main component of the parasympathetic nervous system, which oversees a vast array of crucial bodily functions, including the modulation of inflammation, the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis, and the regulation of food intake, satiety, and energy homeostasis.

Moreover, the vagus nerve plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders and obesity, as well as other stress-induced and inflammatory diseases.4

Balance in the Gut Microbiome is Key

Our GI tract is also home to trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, protists, viruses, fungi, and yeasts, as well as helminths or parasites in some individuals, collectively termed the microbiome. In healthy individuals, these microorganisms live in relative balance with one another and influence activity in the GI tract, in addition to influencing overall health, including the brain and nervous system.

Many things can cause shifts in the ecology or terrain of the GI tract and the abundance of various microorganisms. These shifts can be positive or negative, depending on what species grow in abundance and which may be lacking.

Diet, nutrient status, medication use, stress, sleep, and immune status can all contribute to the overall health and function of the microbiome.

The Gut and Neurotransmitters

Circling back to our enteric nervous system, the brain can “talk” with the gut through chemicals known as neurotransmitters. The ENS produces more than 30 neurotransmitters.4 They have many roles in the brain and body, including stress responses, alertness, mood, and emotions.

Additionally, the GI microbiota can produce neuroactive compounds such as

- Neurotransmitters, such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), noradrenaline, dopamine, and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT))

- Amino acids, for example, tyramine and tryptophan

- Microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids and 4-ethylphenyl sulfate2

The gut is the largest producer of serotonin, which has been recognized for decades as an important signaling molecule, playing an important role in the production of pro-inflammatory mediators from immune cells and providing neuroprotection in the ENS.5

Further, certain fibers in our diet make their way down the GI tract to where bacteria can ferment them to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate. While research shows these SCFAs affect metabolic health and inflammatory balance and support gastrointestinal function and barrier integrity, they can also cross the blood-brain barrier and impact cognitive function.6

Threats to Gut Barrier Integrity

The gut microbiota can also influence gut barrier integrity that controls the passage of signaling molecules from the gut lumen to the lamina propria, which contain immune cells and terminal ends of ENS neurons, or to portal circulation. Gut barrier integrity can become disrupted in some neuropsychiatric conditions, such as anxiety, autism spectrum disorder, and depression.

Within the nervous system, stress can activate the HPA axis response that involves neurons of the hypothalamus that secrete hormones such as corticotropin receptor hormone (CRH) into the brain or the portal circulation. These hormones, in turn, trigger the release of the adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), which then initiates the synthesis and release of cortisol. Cortisol regulates neuroimmune signaling responses that, in turn, affect intestinal barrier integrity.

Stress hormones, immune mediators, and CNS neurotransmitters can activate neuronal cells of the ENS and afferent pathways of the vagus nerve, which can change the gut environment and alter the microbiota composition.2

These impacts on gut barrier integrity are important to consider as research has shown a relationship between poor gut health, the microbiome, and mental health.

Understanding (and Avoiding) Dysbiosis

Dysbiosis is defined as an “imbalance” in the gut microbial community that is associated with disease. The imbalance could be due to the gain or loss of community members or changes in the relative abundance of microbes.7

Dysbiosis can translate into altered gut functioning, impacting the production of neurotransmitters and inflammatory mediators and ultimately contributing to the onset or progression of mental health disorders (anxiety and depression), neurodegenerative diseases,and inflammatory bowel conditions.8 Poor diet, environmental toxins, stress, and overuse of antibiotics and medications are factors that can cause or contribute to the development of dysbiosis.

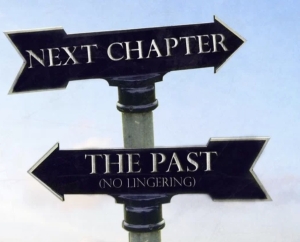

However, there are many things we can do to support a healthy microbiome and encourage an optimal ecology in the GI tract for these microbes to find balance and positively influence the gut-brain axis.

Consuming fermented foods and beverages rich in live probiotic microorganisms or taking probiotic supplements may improve psychological and cognitive functions, according to research.9 As noted earlier, fiber-rich foods, especially those with prebiotic fibers, allow microorganisms in the gut to ferment these, producing secondary compounds which provide us with benefits and support the growth and abundance of the microbes. A flourishing, balanced microbial ecology, in turn, may support the gut-brain axis and mental well-being.10

Additionally, consuming a diet that is rich in polyphenols found in a wide variety of plants has been shown to affect gut health and the microbiome positively and has been shown to have neuroprotective properties as well.11

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352289516300509?via%3Dihub

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352289516300509?via%3Dihub

- https://gut.bmj.com/content/47/suppl_4/iv15

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044/full

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28288510/

- https://www.wageningenacademic.com/doi/10.3920/BM2020.0057

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780128099544/physiology-of-the-gastrointestinal-tract

- https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/6/2099

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13668-020-00313-5

- https://www.eurekaselect.com/article/103524

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0963996921000880?via%3Dihub